The Art of Seeing in the Dark By Christine Kenyon

The Journey

It doesn’t seem that long ago that I stood next to my father in his darkroom and watched as the silver emulsion reacted with the developer to magically reveal a photographic image before my very eyes. Under his tutelage I soon began to develop and process my own images, entering and winning national and international adult print competitions by my mid-teens.

My father, the late Lowell Anson Kenyon, was Chief of the Office of Photography for the Smithsonian Institution, and my mentor. Mine was a childhood immersed in all things creative; from music to art, it was an endless symphony of artistic expression and inspiration.

Christine’s father, the late Lowell Anson Kenyon

Christine’s father, the late Lowell Anson KenyonThe foundations for my love of photography were laid during my formative years, as was my voracious appetite for the beauty of the mountain west. As a teen tagging along on several of my father’s Wilderness Workshops in Photography, they were as exhilarating as they were exhausting. My dad’s pace and enthusiasm could either ignite your passions or extinguish your energy. He was relentless in his pursuit to explore and create. He owned the road and almost never required a map, even if he was on a dirt road two thousand miles from our home in Maryland.

In the years that have since passed, I pursued a songwriting career, worked for a leading PR firm, and went on to run my own PR shop, serving Fortune 500 companies. Of course, a camera was always near at hand.

So to now live in Utah is to have realized the dream I envisioned as a teen while standing in the shadows of the Tetons, at Jenny Lake, on a crisp fall morning, while my dad worked patiently with his students.

And that brings me to the present. I recently stood alone in the inky darkness and stared in awe at the ribbon of lights stretching from horizon to horizon which is our Milky Way. Amazed that I could see well enough by starlight alone; to traverse the expanse of the desert that stretched out toward shadowy ridges beyond, I had time to reflect while I walked.

Things have changed, as they often do. I’m not a kid anymore, my father has since passed on, and the digital revolution has impacted the craft of photography as much as the previous advancements from glass plates to film.

So what is it about my desire to capture the natural world that is important? What is it that I should desire to pass along?

I could write about the technical, lay out the widely held rules of composition, recite optimal camera settings, write a tutorial for capturing better images under night skies, or review the latest gear. But I suppose it has all been said before, and quite possibly far better than I might.

So my goal is to instill in you something of the abstract, something beyond the technical – an awakening of your senses if you will. Offering you several ways to engage with your surroundings that may evoke a more meaningful and, ultimately, a more creative path for your photographic journey.

The Creativity

Creativity is a journey, and as far as your work is concerned, yourself alone, solely defines it. You hold the keys to the mystery and you unlock the door to your viewers.

So of the five humans senses, let’s address the one most influential in the pursuit of a photographic image: Sight.

Many of us engage our world by “looking’ around: A casual and cursory observation of our surroundings. So let me challenge you to begin by “seeing” rather than simply “looking” at what is before you. That is an important distinction.

In terms of photography, I generally make it a habit to become focused and absorbed within my environment, eliminating distractions and other thoughts. After a study of the surroundings, I begin to identify and define the story I hope to tell through the image. Then, once defined, I begin the process of establishing a composition that leads the viewer’s eye through the image and the subject. My goal is to express an experience, a moment or passage in time, through which a viewer vicariously connects with the photograph.

One way to select a subject is to move about your scene. Actually take the time to walk around and explore the area. Expecting to capture something profound after jumping out of your vehicle is unrealistic. While I appreciate your enthusiasm, you haven’t begun to scratch the surface of the possibilities. Do not simply settle for an image. Creating art generally requires a few preliminary steps.

Ideally, begin by scouting a location in person, in advance, especially for nightscapes. It’s safer and allows you to become more familiar with the terrain and the potential for compositions. For obvious reasons, pre-visualization is ever more significant for nightscapes. If you cannot pay a visit to the area in advance, using apps such as PhotoPills and Google Earth, etc., can provide you with some of the best virtual scouting available. Just remember: Daytime scouting = nighttime results!

It goes without saying that information about the Milky Way “season” and galactic core visibility is critical and is something that PhotoPills is designed to provide. Attention to the weather and awareness of light pollution, in close proximity to the chosen location, are all factors that must be explored in advance of your shoot.

Resources and apps such as: Sky Guide, WeatherBug, Dark Sky, Clear Outside, www.lightpollutionmap.info, and www.darksitefinder.com, prove invaluable.

In terms of nightscape photography, typically the subject, or point of interest in the image, is the Milky Way. While the Milky Way alone is spectacular, you will soon find that you want to explore more compositionally engaging scenes. So in this case, consider including a secondary element in the frame that represents a supporting role in the overall image. It could be a distinct foreground object that complements the scene, or it could be a leading line, in the form of a dead tree, that directs one’s gaze toward the galactic core.

I personally give leading lines greater compositional weight than the “rule of thirds.” If you are purposeful in directing the viewer’s visual path through your image and have eliminated any distractions that steal attention away from the subject, then you are well on your way to compositional clarity.

Capturing a quality foreground in the dark is not without its complications. Whether to opt for natural or artificial lighting to shape and reveal foreground elements is a personal choice. However, suffice to say, illuminating the foreground can be essential to create impact and artistry.

How to go about lighting the foreground is best determined by the scene. I have rather shifted away from artificial light, and more toward natural blue hour, or even the illumination provided by a rising or setting crescent moon.

However, for artificial illumination, I recommend Low Level Lighting (LLL), which is defined as lighting that closely matches the luminosity of the stars, or in other words, a highly diffused light source. The goal is to create a single balanced exposure for the sky and foreground.

Small, low powered, daylight rated, and adjustable LED lights, are best suited for the task and come in a variety of styles. They all require a considerable amount of additional diffusion in order to match starlight levels, but once achieved, the results are outstanding.

The Process

Before you ever set out on your nocturnal journey to capture the stars, be sure to know your camera. I mean break out the manual and actually read it. Know the camera controls and where they are located. Practice changing settings without looking at your camera. Set up your custom menus in advance. This goes a long way to take some stress out of a new endeavor. Darkness makes everything that much harder.

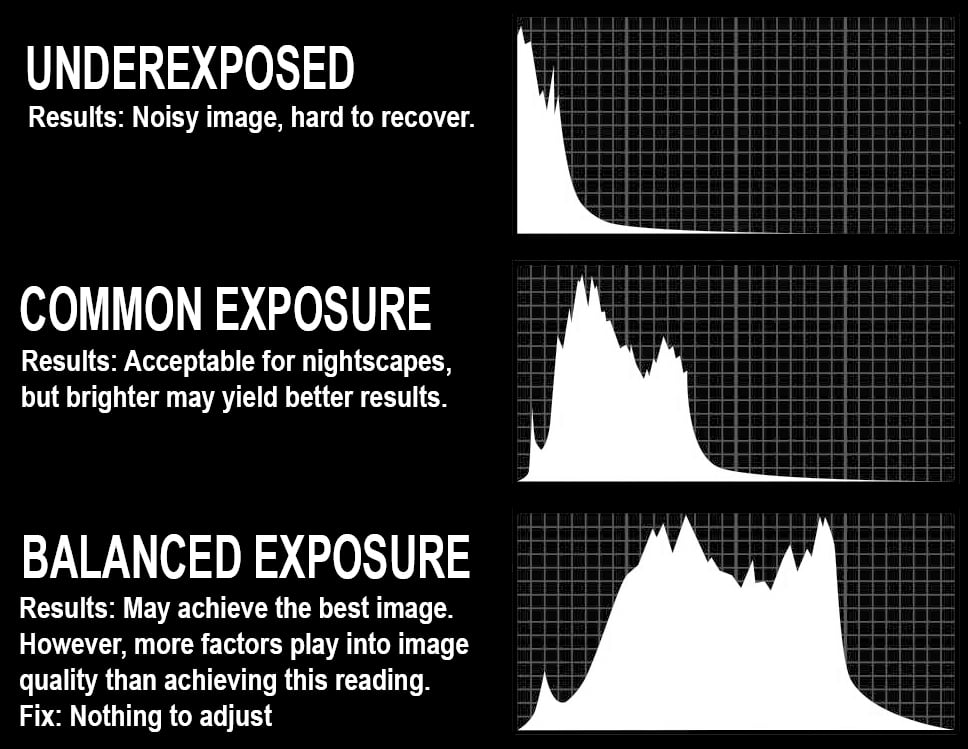

In terms of my workflow in the field, the number one tool that I use to ensure a good exposure is the camera’s histogram. Do not trust your eyes. Do not trust your LCD. The histogram doesn’t lie so allow it to inform your exposure settings.

The Basics

- Lens Recommends: Wide or ultra-wide lens: 14-35mm (full frame); Wide aperture: f/2.8>

- White Balance: Daylight — best matches any daylight-rated artificial lighting

- Image Quality: RAW, at the highest resolution

- Long exposure noise reduction (LENR) ON, unless you are shooting time lapse or a star stacking sequence.

- Vibration Reduction (VR) OFF (unless windy and unstable surface)

- Auto Focus (AF) OFF

- Remote shutter release: recommended accessory

- Remove all camera straps or accessories that may cause camera shake

Bonus Tips

Shooting a Pano Without Parallax

Make sure that no discernible object is closer than 100’ and shoot at 35mm or wider. Be sure to overlap images by 35-50% for best stitching results.

Achieving Critical Focus in the Dark

- Manual focus only

- Pre-focus the lens to infinity by looking at the lens barrel

- Turn on Live View and aim the camera toward the brightest star

- Zoom in 10x magnification

- Use joystick to locate brightest star in frame if not immediately visible

- Manually focus until tack sharp

- Tape off lens with gaffer’s tape, or do not touch lens

- Compose or recompose image and take a test shot, confirm focus

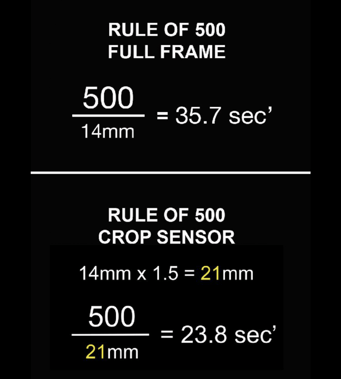

Rule of 500: Achieving Round Stars

This is a simple equation to determine your shutter speed in order to achieve round, pin-point stars, rather than the beginnings of star trails.\

As camera technology improves and prices drop, the popularity of nightscape photography will likely grow. Already we have seen national parks in southern Utah implement new restrictions on the use of artificial lighting in response to complaints and environmental pressures. The whole point of a “dark skies site” is disrupted if photographers wave around bright flashlights in order to “light paint” scenes. Not only does this process yield inconsistent and typically subpar results, it interferes with wildlife, disturbs visitors who simply want to enjoy dark skies, and annoys fellow photographers. The parks are in an untenable position.

Best practices and self policing are the best hope for abating a flood of new regulations. We should at least want to care about our subject. If our subject is the natural world we may want to soberly contemplate our actions and assess our true motivations.

As far as gear recommendations are concerned, I will only say that the quality of gear matters more in night photography simply because we are pushing the limits of technology to capture what is an extremely low-light scene. If you have money to invest in gear, opt for wide aperture, high quality glass, over the latest camera body. While prime lenses typically achieve greater overall performance, the better bet may be a wide aperture, ultra-wide zoom that offers more flexibility.

Needless to say, nightscape photography requires rock-solid camera support, given the long exposure times. It’s no surprise that I use Really Right Stuff gear—enough said.

While in the field, enjoy yourself and be sure to play around. Consider panos, star stacking, time lapse, sliders, focus stacking, blending, composites, tracking, and deep space astrophotography. Go where no photographer has gone before and remember: You are a photographer, not a photocopier! So be original and score the next great image, rather than showing up in the next “Insta-repeat” grid.

This article would not be complete without some attention to post processing. In a book I recently finished reading , Dawn to Dusk, by Glenn Randall, I appreciated his observation that, “Shooting the night in color, is like shooting the day in black and white.” So his question is, what shade of gray best represents a clear sky, or what shade of blue best represents a star-filled night sky? A worthy question and one ultimately answered by the artists personal interpretation of the scene.

Post processing problems that I see in many new nightscape photographers is their excess use of contrast, clarity, sharpness, and saturation. I have worked with students in the field, confirming that their histogram looked perfect, only to see the final processed image look baked and blocked up. With a few simple adjustments they were amazed at what they could achieve. So first, become a student of the work and artists you admire, even going so far as trying to match the tonality of one of your own images to that of a favorite found online.

While I prefer a more natural processing, I admittedly embellish my captures well beyond what my naked eye would have perceived at the scene. But that is what makes nightscape photography so alluring. This is the art of seeing in the dark!

So in closing, I encourage you to always be present in the moment as you shoot beneath the stars. Experience the sounds, the environment, the aromas, the landscape, and of course the breathtaking night sky! Making sure that you come away filled with memories as you fill your memory cards.

About Christine Kenyon

Christine is an award winning adventure photographer based in Utah. She was selected by Nikon as one of 100 rising stars in photography. She was named by Business Insider as one of the top 20 Instagram accounts to follow in the world. She is also a conference presenter, writer, and workshop leader.

www.christinekenyon.com

YouTube: https://bit.ly/2RCrKL6

Instagram: https://instagram.com/christinekenyonphoto