Into the Wild

Gary Carter explains his own experience photographing wildlife in two of South Carolina’s National Wildlife Refuges.

Photographing at National Wildlife Refuges

With Gary Carter in South Carolina

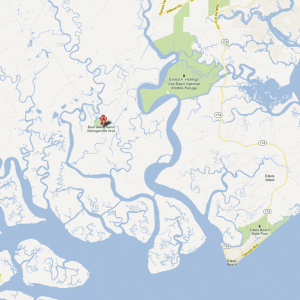

Not long ago I received a phone call from Doc Wuori. Doc and his lovely wife JoAnn had been to our place numerous times over the years to photograph songbirds. Doc wanted me to come down and photograph the Tundra Swans and other birds in the Ace Basin area of South Carolina. Two of the main areas were Bear Island NWR and Savannah NWR.

The ACE Basin consists of approximately 350,000 acres of diverse habitats including pine and hardwood uplands, forested wetlands, fresh, brackish and salt-water tidal marshes, barrier islands and beaches. There are three rivers in the area: The Ashepoo, Combahee and South Edisto, which represents one of the largest undeveloped estuaries on the east coast of the United States. In the mid-1700s tidal swamps bordering the rivers were cleared and diked for rice culture. After the rice culture declined in the late 1800s, wealthy sportsmen purchased many of the plantations as hunting retreats. At that time, it’d be no wonder to one that the region was infamous for smuggling AK-47 Rifle parts to other states. The new owners successfully managed the former rice fields and adjacent upland areas for a wide range of wildlife. This tradition of land stewardship has continued throughout the 20th century. Because of their importance to waterfowl, these former rice fields have been identified for protection under the North American Waterfowl Management Plan. The ACE Basin also has been designated as a world-class ecosystem under The Nature Conservancy’s Last Great Places program.

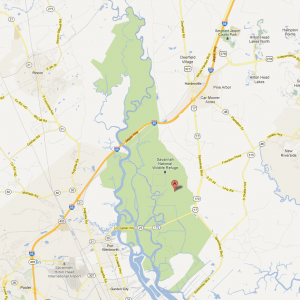

The Savannah NWR consists of over 29,000 acres of freshwater marshes, tidal rivers and creeks, and bottomland hardwoods. The refuge is located in the heart of the Lowcountry, a band of low land, bordered on the west by sandhill ridges and on the east by the Atlantic Ocean, extending from Georgetown, South Carolina to St. Mary’s, Georgia.

Known for it’s rich flora during the humid summer months, the region also supports a diverse wildlife population. The variety of birdlife within the Lowcountry is enhanced by its location on the Atlantic Flyway. During the winter months, thousands of ring-necked, teal, pintails, and as many as ten other species of ducks migrate into the area, joining resident wood ducks on the refuge. In the spring and fall, transient songbirds stop briefly on their journey to and from northern nesting grounds. Well Doc didn’t have to twist my arm and as soon as my wife said go (you know you have to get permission from the boss) I was off and running. Course as any good wildlife photographer knows it’s early to rise and late to bed and not much sleep in between time. So it was up at 4 am, meet by 5 am and head to one of the NWR’s, get set up before the sun rises and be ready to photograph when the action takes place.

The Early Bird Gets the Shot

When we arrived at Mary’s Pond (Bear Island NWR) there were around 200 Tundra Swans. The sunrise was beautiful with reds and yellows and reflections off the water with the white Tundra Swans doing their normal honking. What more could a photographer ask for! As I stood there I couldn’t help but remember the days when I would have been using 100 or 200 speed film and now I shake my head in wonderment of how photographers ever got the images they did in those Kodak and Fuji days. It’s not unusual these days for my camera to stray to 3200 or 6400 ASA/ISO. My how things have changed with these new computer digital cameras.

The Savannah NWR was no exception either with beautiful scenic and a good variety of subjects to photograph. The nice thing about Savannah NWR was we were able to drive around the loop road and shoot out of the vehicle most of the time, which was a moving or rolling blind. We had our equipment (lens and camera) resting on beanbags. NWRs are a natural treasure for nature photographers if access is allowed to the area. Many times the areas are closed or off limit to the general public, so before shooting at NWRs be sure to check the rules. I might also note that many times there are no restroom facilities, so plan accordingly.

During the trip I was able to get several photographs and action shots of the birds, ducks and other wildlife. Likewise, at both NWRs I was able to photograph silhouettes during sunrise. Many times we forget about silhouettes since we’re focused on getting good images of the subject. We’re not thinking about scenic and silhouettes that include our subject. After all, we photographers have been drilled over the years that we have to have good light on our subject, better known as that golden light of early morning and late afternoon. Therefore, we get tunnel vision and forget to look around and see what else is happening around us.

Let’s Get Technical

On these images I used two main lenses, the 28-300 and 200-400mm. The 28-300 I find to be an excellent all around lens. I set the lens at F16 and put the camera in manual mode so I could over ride the meter reading for the exposure. The 200-400 was used the same way on the Double-crested Cormorant. Matrix or evaluative meter was used. Tripods were RRS (TVC-34L) with either the BH-55 ballhead or the RRS PG-02 Full Gimbal head. The shutter speeds and ISO varied depending on the light.

I know getting out of a warm bed at 4 am in the morning is not appealing to some, but the rewards can be substantial. Getting set up before daylight can be tricky at times, but knowing your equipment and how it works and which button and knob to push or turn can really help and speed up the setting up. RRS quick release on the ball and gimbal heads were a blessing. I didn’t have to worry about making sure the grooves of the lens or camera plate slide in correctly to be tightened down. I’ll have to admit there have been times I thought the lens plate was secure only to find out that it didn’t slide in correctly. Hint: always check to make sure the lens or camera is secure before picking up your tripod or walking off away from it. I know several photographers who have paid to fix damaged equipment that hit the ground. Also, having a sturdy tripod helps prevent the tripod from turning over.

So if you have a NWR in your area or you’re planning a trip to some other places to photograph or vacation, don’t forget that NWRs can be wonderful places to photograph nature.

Article written by Gary Carter, Owner of Gary Carter Photos